John Erath

Union Success in the Civil War and Lessons for Strategic Leaders

07 àïðåëÿ 2015

On April 10, 1865, Robert E. Lee wrote a letter to the soldiers of his army that began, “After four years of arduous service, marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been forced to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.”1 At this moment, the Civil War essentially ended in victory for the Union, and the process of reuniting the United States of America began. Lee’s immediate view of the circumstances, that the Confederate armies had done everything possible but were overmatched by Northern numbers, provided a means by which his veterans could feel that they had served honorably, but it was challenged almost immediately by other Confederate military and political leaders who blamed instead such factors as incompetent government, social divisions, and political squabbling for their defeat. The Confederacy, many felt, would not have embarked on a war it could not win.2 Indeed, its success in repelling invasions over the first 2 years of the war led many to believe that the war had almost been won.

A century and a half later, there remains considerable debate among historians as to the reasons for the outcome of the Civil War. Many explanations have been proposed for the Union victory: political, economic, military, social, even diplomatic.3 Strong cases can be made as to why each was important to the Confederacy’s downfall. Yet the key to victory was found in 1864, after President Abraham Lincoln appointed General Ulysses S. Grant the commander of all Union forces. In concert with Lincoln’s other strategic efforts to weaken the Confederate will to resist, Grant devised a military plan that ultimately gave Lee no choice but to surrender. Although there was no written plan, Lincoln and Grant combined the separate elements of Union power in a complementary way to make continuing the war more painful to the Confederate population than rejoining the Union. This comprehensive strategy, which included political, economic, and diplomatic elements as well as military operations, led to victory.

By the early 20th century, however, a consensus had emerged among many Americans that endorsed General Lee’s view of how the war ended: the Union simply had advantages in population and economy that made victory inevitable. The United States has enjoyed such advantages in every subsequent conflict and has generally sought to take advantage of them. Yet Lee’s perspective was simplistic. When American leaders have been successful in war, it has been because they, as did Grant and Lincoln in 1864, implemented an overarching strategy that incorporated all aspects of U.S. power to achieve results; brute force and abundant resources alone are most often insufficient to achieve the desired outcome. By orchestrating a complete national strategy, Lincoln and his top general, Grant, provided the template for American success in war—a template that 21st-century strategic leaders would be well advised to follow.

Grant Changes the Game

In February 1864, Lincoln appointed Grant General-in-Chief of the Union armies, and they began piecing together the means to win the war. For over 2 years, Lincoln and his commanders pursued objectives without a unifying strategic goal. The only experience of strategy for most Americans was the war with Mexico (1846–1848) against a dictatorship in which the strategy was straightforward: defeat the army and capture the capital. More comprehensive means were needed against a large democratic opponent. Despite a string of Union successes in mid-1863, including Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and the capture of Chattanooga, Union prospects remained uncertain, and the new year would include elections in which voters unsatisfied with the progress of the war could support an accommodationist government. In the east, Army of the Potomac Commander General George Meade had not followed up the defeat of the Confederate invasion of the North with significant offensive operations, and Lee’s army remained a potent force. In Tennessee, Union forces had advanced about 70 miles in the previous year but suffered a major reverse at Chickamauga. In the West, an epic blunder had allowed Grant to capture a small Confederate field army at Vicksburg and open the Mississippi River to commerce, but Confederate cavalry raids threatened supply lines and kept Union forces from straying far from rivers, thereby preventing the occupation of much territory. In short, over 2 years of bloody war had resulted in the liberation of exactly one state (Tennessee) and some small areas near waterways.4 It must have seemed to many in the North that subduing the entire Confederacy would be a task beyond the scope of Union resources. On February 3, 1864, the New York Times wrote that more men would not be enough to win the war and could never occupy all Southern territory.5

There were three main reasons for the Union’s slow progress in the war up to 1864. First was the superiority of the defense in 19th-century warfare. A generation earlier, Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz, reflecting upon his experiences in the Napoleonic Wars, had called defense “the stronger form of waging war.”6 The introduction of the rifled musket in the 1850s amplified the advantage of the defense by more than tripling the effective range of infantry. When coupled with improved methods of field fortification, Civil War–era armies were almost invulnerable to frontal assault, as the Union learned at Fredericksburg and the Confederacy at Gettysburg. Even if one side could manage an attack on an unprotected flank, armies had a degree of tactical flexibility that allowed withdrawals in good order to strong defensive positions. Lee’s tactical masterpiece at Chancellorsville forced a Union retreat across the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers but did not destroy the Union army; in fact, Lee suffered proportionately much higher losses in victory.7

The Confederacy also possessed the advantage of being able to concentrate forces in response to Union offensives. In addition to operating on interior lines, Confederate armies were able to make use of railroads to move forces to locations threatened by Union operations. The Confederates used their strategic mobility to its best effect during the Chickamauga campaign, when they came closest to destroying a Union army after achieving local superiority through strategic movements of troops. Any effective Union strategy for 1864, therefore, would have to address the potential for such concentrations.8

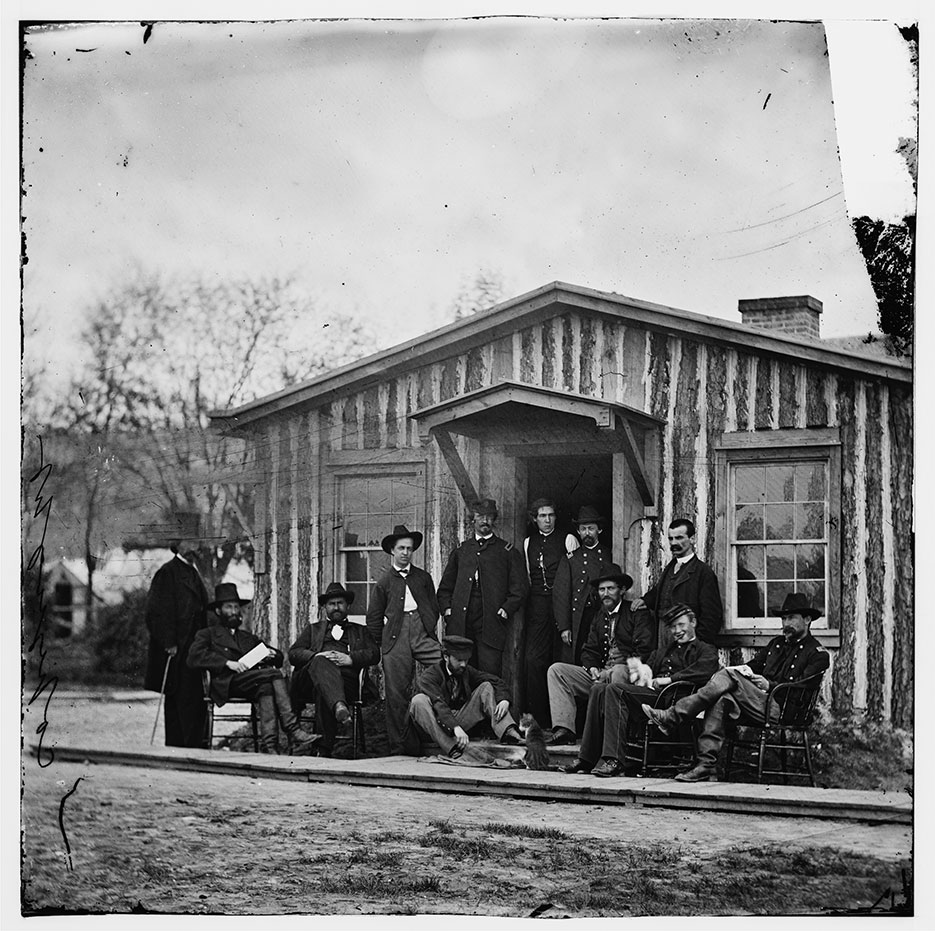

Members of Grant’s staff during main eastern theater of war, siege of Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864–April 1865, with photographer Mathew Brady standing at far left (LOC)

Finally, the Union effort was hamstrung by logistical difficulties. Civil War armies required huge amounts of food, fodder, ammunition, and other equipment. Large land areas and poor roads, especially in the West, meant that armies were confined to operating near rivers and railroads. Even railroads were highly vulnerable to raids from cavalry and irregular forces. Grant’s first effort to approach Vicksburg had been defeated almost bloodlessly by Confederate cavalry raids. When he later operated successfully against the city, almost half of Grant’s overall forces remained in Memphis and western Tennessee to protect his supply lines.9

Given these constraints, it would seem that Civil War armies would have had the most success by avoiding battles, except on unusually favorable terms and using the strategic mobility afforded by railroads to interdict enemy logistics. While commanders, particularly the Confederates in the West, sometimes used this approach, both armies, as well as their civilian leaders, still looked at battle as a path to victory.10 Civil War commanders therefore faced almost continual pressure, from Bull Run until the end of the war, to seek battle as a means to destroy opposing armies, despite mounting evidence of the near impossibility of a Napoleonic battle of annihilation. Lee thoroughly outmaneuvered Joseph Hooker at Chancellorsville, but he made no further progress once the Union army established a firm defensive position. At Stones River in late 1862, both armies outflanked each other but ended up pounding on their opponents’ positions for little gain. In both the North and South, public attitudes on the progress of the war were disproportionately shaped by the results of battles, especially those in the eastern theater. General Ambrose Burnside’s disastrous attack at Fredericksburg was in part motivated by political pressure to take the offensive against Lee. In 1864, Confederate President Jefferson Davis removed Joseph E. Johnston from command of the Army of Tennessee and appointed John Bell Hood to force attacks on William T. Sherman’s army, an action that hastened the fall of Atlanta and may have helped Lincoln’s reelection. On the eve of the war’s most complete battlefield victory, Nashville, Grant went so far as to order the relief of his field commander, General George Thomas, for being slow to attack. Fortunately, the order did not arrive until after Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland had routed its opponent.11

The task that faced Lincoln and Grant in early 1864 was formidable. Both understood that the Union would not be able to occupy all of the South in the face of armed resistance—the aim of earlier Union strategy—or to destroy its armies by attacking them in the field. A purely logistical strategy, similar to that proposed by General-in-Chief Winfield Scott’s much-derided “Anaconda Plan,” would be difficult in an agriculturally self-sufficient area, and the South’s rapidly developing war industries gave it the capacity to resist potentially indefinitely. By 1863, initial shortages of war materiel, especially weapons and ammunition, were largely a thing of the past; the army Lee took north in June was roughly proportionate to its opponent in numbers and quality of artillery, and almost all of its infantry had modern rifles.12 The Union did, however, possess several advantages that could be brought to bear. Abraham Lincoln had proved an outstanding wartime political leader and by 1864 had in place a strong leadership team, including Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Secretary of State William Seward, Army Chief of Staff Henry W. Halleck, and Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs. The Union Army benefited from outstanding management and supply as a result. Lincoln’s political skill had maintained consistent support for the war effort in Congress and patience among the Northern public when faced with military reverses. The Emancipation Proclamation was a decisive political stroke that had associated Union war aims with moral objectives. The Union also had, after much trial and error, placed most of its military forces in the hands of skilled leaders who had come to understand 19th-century war and were at least equal to their Confederate counterparts.

Grant’s goal was to find ways to use these advantages to overcome the factors that had previously thwarted Union efforts. Without an overarching strategic focus, the Union directed its actions at targets of opportunity—armies or geographic features—for short-term objectives rather than to win the war. Prior to 1864, the political process too often drove military decisions, leading to ill-advised attacks, such as those at Bull Run and Fredericksburg. Union generals did not receive clear strategic guidance and often had to pursue multiple objectives, including trying to destroy Confederate armies, occupying territory, building railroads, and protecting supply lines. After the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863, Grant’s army spent most of the summer relatively inactive, except for some local raiding, without an immediate strategic objective.

Piecing the Elements of Strategy Together

It is difficult to evaluate the 1864 Union strategy because it never appeared as a single document, nor was it articulated as a whole in Grant’s memoirs or those of other Union leaders. Instead, it must be pieced together from what those involved in its creation have written. Grant’s memoirs focus on the military operations that he controlled. At the same time, the Republican political leadership shaped a plan to win reelection while the State Department sought to increase the Confederacy’s isolation. As President, Lincoln had to coordinate these efforts as elements of a complete strategy that complemented Grant’s military efforts. Grant had likely not been exposed to Clausewitz, but the Prussian theorist would have recognized in Grant’s strategy the targeting of the enemy’s center of gravity the key to his resistance. Based on his analysis of the Napoleonic Wars, Clausewitz believed the center of gravity generally to be the army, although sometimes it was the national leadership and the nation’s capital city. The Civil War was the first conflict since ancient times between two democracies (or perhaps two versions of one democracy).13 As such, the center of gravity had to be different from those found in European monarchies. Grant and Lincoln intuitively grasped that the only way to win the war was to break the support of the Southern population for continuing its war effort. In Clausewitzian terms, the Union identified public support for the war as the Confederate center of gravity, providing a formula for those seeking to defeat democracies to this day. The Confederates, to some extent, figured out this formula before the Union did. One of Lee’s motivations for the second invasion of the North in 1863 was to seek a victory on Northern soil in hopes of inducing the Northern public to believe that the war was unwinnable.

Grant’s focus in the broad Union strategic construct was the military effort aimed at the Confederate armies and their sources of support. Grant and his top subordinate, General Sherman, formed their operational plans based on previous experiences, including trying to avoid frontal attacks such as Fredericksburg or Sherman’s unsuccessful assault on the Chickasaw Bluffs near Vicksburg. The defeat at Chickamauga led to heightened concerns that the Confederates would again move troops from one army to another to gain local superiority. Grant wrote that his plan was for Union forces to concentrate against the two main Confederate field armies. He ordered Sherman, commanding in the West, to “move against [Joseph E.] Johnston’s army and break it up,” while telling Meade in Virginia that Lee’s army was his objective. Grant also included smaller forces, in Tennessee, West Virginia, and tidewater Virginia, in his plan by directing them against key production and transportation facilities that supported armies in the field. Once Sherman captured Atlanta, the bulk of his forces became in effect a large raiding party aimed at damaging Confederate means of supply. Historian Archer Jones refers to the Union concept as a “raiding logistics strategy,” in which opposing armies would be deprived of the means to continue operating, and attributes Union victory to its implementation.14While the Union’s increased focus on Confederate sources of supply played a role in the Confederate defeat, it was not alone decisive. To the end of the war, Confederate armies maintained the ability to resist, and although they suffered shortages, they managed to obtain what they needed to keep fighting.

While Grant was planning his 1864 campaigns, Lincoln took political measures to promote Union success. With Lincoln’s Democratic opponents planning to run on a peace platform, reelection was vital to overall Union prospects, but a steady stream of indifferent military news made a Lincoln victory seem unlikely until weeks before the election. The political and military policies were therefore dependent on each other: to win the war, the Union needed Lincoln’s reelection, but to win in November, Lincoln required military success. The war’s most important policy step, the Emancipation Proclamation, had been issued a year earlier and had the effect of solidifying the moral basis for the war as well as opening the door to the recruitment of significant numbers of black troops. Lincoln’s 1864 publication of the relatively mild terms under which Southern states would be readmitted into the Union (which, as with the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln did without congressional authorization), while initially greeted with scorn, served to provoke debate in the Confederacy as to whether further resistance would be worse than submission.15

The Union’s economic policy likewise had the effect of making life more difficult in the South. By 1864, the majority of Confederate ports were in Union hands, but even in 1864, 84 percent of ships attempting to run the blockade succeeded. In any event, against an agricultural society such as the Confederacy, a blockade was unlikely to produce much real hardship. Although the South initially lacked war materiel, by 1862 it developed production facilities adequate to supply its forces with arms and ammunition, so as not to depend on imports.16 (When the U.S. Army opened its new Infantry Museum in Fort Benning, Georgia, in 2009, it “guarded” the entry to the main exhibits with 2 12-pounder cannon produced by Georgian foundries during the war.) The blockade did have two important effects. First, it restricted the supply of luxury goods being imported, creating an impression of hardship, especially for the ruling class. It also deprived the Confederate government of customs revenues, the primary source of government income in the 19thcentury. The most severe economic blow to the Confederacy was self-inflicted. By cutting itself off from the financial system of banks, the South deprived itself of necessary capital and, by financing its military with unsecured paper money, started itself down the road of hyperinflation.17

Other aspects of U.S. policy also contributed to achieving the conditions for victory. From the beginning of hostilities, Union diplomatic efforts aimed at preventing foreign recognition of the Confederacy. Secretary of State William Seward instructed U.S. diplomatic missions to inform foreign governments that the conflict was not legally a war, but an internal dispute, in effect declaring that any recognition of the Confederacy would be contrary to international law. Seward was concerned because European governments, particularly the United Kingdom, viewed the United States with suspicion. The American minister in St. Petersburg, Cassius Clay, gave Seward his view of the sentiment in Europe in 1861: “They hoped for our ruin. They are jealous of our power.”18 The Emancipation Proclamation proved the key diplomatic stroke of the war as it equated support to the Confederacy with support for slavery, an unacceptable stance in most of Europe. While there may have been some sympathy for the Southern cause, or at least desire to see the Union broken, the political cost of support to the South had become too high. Confederate leadership had begun the war with high expectations of European support. When it did not materialize, the South’s sense of isolation increased.

The Union’s final strategic advantage was in how its policies contributed to maintaining popular support while eroding it in the South. The Lincoln administration by 1864 had developed methods of dealing with the press to obtain favorable coverage from many of the major East Coast newspapers. When the Army of the Potomac was locked in a bloody stalemate at Spotsylvania in May 1864, the New York Times reported, “The terrible pounding the rebels received . . . has compelled them to fall back. . . . Lee’s retreat [is] becoming a rout.”19 The appointment of Grant to overall command was as much a public relations move as a military one and was intended to show the Northern public that the Union now had military leaders comparable to those of the South. Grant, in fact, was under a great deal of pressure to take personal charge of the Virginia theater to confront Lee directly. Because, unlike previous Union commanders, Grant did not seek to win the war through a decisive battle, he did not undertake the sort of risky operations that had led such commanders as John Pope, Ambrose Burnside, and Joseph Hooker to defeat. Conversely, the fact that Lee could not clearly win a battle against Grant had a significantly negative effect on Southern morale.20

Ruins of Richmond, Virginia, 1865 (NARA/Mathew Brady)

Turning the Tide

Even though the Union employed the elements of a comprehensive strategy in 1864, victory still proved difficult. The simultaneous offensives of the main armies succeeded in preventing Confederate concentrations but did not result in the battlefield victories the public was expecting. In the east, Grant and Meade faced Lee in a relatively small theater where scant room for maneuver meant the armies remained in nearly constant contact, building huge casualty lists for little tactical advantage. In the West, Sherman’s army avoided frontal attacks by using the larger area of operations to outflank Confederate positions. Although he advanced against Atlanta, the Northern public again expected successful battles.21 Incompetent political appointee generals stymied Grant’s plans to disrupt Confederate logistics with raids in the Shenandoah and up the James River toward Richmond.22 In the summer, there was considerable doubt that Lincoln could be reelected; John C. Fremont even mounted a challenge for the Republican nomination. The Democrats approved a peace platform, in effect declaring the war unwinnable.

Meanwhile, the war was being won. After spending May and June repeatedly trying to move around Lee’s right flanks only to encounter entrenched Confederate defenses, Grant managed to surprise Lee by bypassing Richmond, crossing the James, and moving on Petersburg. The capture of this city would cut most of the supply lines to Richmond and Lee’s army and potentially force Lee to attack at a disadvantage. Only dawdling by subordinate commanders kept the Union from seizing Petersburg, but Grant still pinned the Army of Northern Virginia in a siege. Neither side wanted this situation. Lee believed that it would be “only a matter of time” before he would be forced to give up his capital.23 The Union leadership, mindful of the siege of Sevastopol in the Crimean War, where allied armies suffered crippling losses taking the city, was concerned that the Army of the Potomac would waste away in the trenches while their opponents remained secure in the city.24 By trapping Lee’s army, however, Grant could dispatch General Philip Sheridan to the Shenandoah, a critical source of supply for the Confederate army. Sheridan won three battles against smaller Confederate forces, giving the Union needed battlefield successes.

At the same time, Sherman approached Atlanta. His Confederate opponent, Joseph E. Johnston, had adopted the same approach the Russians had in 1812, trading territory for time and lengthening the enemy’s supply line. By the time Sherman neared Atlanta, almost 30 percent of his original strength had diminished from attrition and the need to protect his line of communications.25 Confederate political leaders had grown impatient with the apparent lack of decisive action, and Jefferson Davis replaced Johnston with John Bell Hood, who had lobbied for the job with promises he would seek immediate battle. Hood attacked three times, and the defensive advantages of Union armies led to three defeats. When Sherman cut Atlanta’s last railroad on August 31, Hood evacuated the city.

Atlanta was an important industrial and transportation hub; its loss, however, had greater significance. The Confederacy still had other operational railroads and could make up much of Atlanta’s production elsewhere, but the city’s fall provided a highly visible sign that the Union was making progress in the war. This apparent progress came at an ideal time in the political season. Together with a continuing economic expansion, military success provided an electoral college landslide. While Lincoln might have won the election without Sherman’s success, it effectively undercut the main argument of Democratic candidate George McClellan: that Lincoln was doing a poor job running the war. With preventing Lincoln’s reelection a key strategic goal of the Confederate government, the election result signified that continuing the fight meant 4 more years of an increasingly terrible war. In South Carolina, Mary Chesnut, the wife of one of Jefferson Davis’s advisors, wrote, “Atlanta gone . . . No hope. We will try to have no fear. . . . We are going to be wiped off the face of the earth.”26

Following Atlanta’s fall, Sherman shifted his operational stance from an offensive against a Confederate army and its base to one of raiding the Confederate heartland without conquering territory. Jefferson Davis approved Hood’s plan to attack Sherman’s line of communications back to Tennessee, not understanding that as a raiding force, Sherman’s army could operate independently of its supply source. Grant ordered forces detailed to protect Tennessee to concentrate at Nashville under the command of General George Thomas, probably the war’s best field commander, to deal with Hood. This move allowed Sherman’s force to become what Grant termed a “spare army.” Its target was not Confederate soldiers, but rather the Southern will to fight. As Sherman put it, “This movement is not purely military or strategic, but will illustrate the vulnerability of the South . . . and make its inhabitants feel that war and individual ruin are synonymous.”27

By the end of 1864, the situation in the Confederacy had changed dramatically. Its armies had been unable to win on the battlefields. The Davis administration appeared increasingly ineffectual. Union armies neutralized centers of production and transportation, leading to shortages for the armies and on the homefront. Union armies seemed to march where they wished without serious opposition, striking at the idea that the Confederate government could perform the most basic of functions: control its own territory. With Lincoln’s reelection, the chance that the North would tire of the war seemed increasingly slight.

At the same time, a political division emerged in the South. At the war’s outset, most of the Confederate leadership would have agreed with Jefferson Davis’s statement that the South had gone to war to preserve slavery. By 1864, with the Emancipation Proclamation issued, much of the Southern population saw the issue differently. Many Southerners had come to consider self-determination and independence more important war aims.28 There had always been a contradiction for the majority of Confederate soldiers who did not own slaves but were fighting for a slave-owning elite’s right to maintain their “institution.” The issue was highlighted on January 2, 1864, when General Patrick Cleburne proposed offering freedom to slaves who enlisted in the Confederate army. Cleburne’s proposal was quickly shelved by his superiors, but the debate as to whether the South was fighting for independence or slavery grew, sapping enthusiasm for continuing the war. To fight the war effectively, the Davis administration had taken centralized authority over war-related industries and railroads. By doing so, however, it alienated the large segment of its population that believed that the war was about states’ rights and freedom from central government control. To maintain a strong military, the Confederate government undermined its own base of support.29

As 1864 ended, the Union clearly held the upper hand militarily. The December 15–16 Battle of Nashville, where the Union achieved the victory of annihilation that both sides sought early in the war, erased any doubts about Northern prospects. For only the second time in the war, an entrenched army was successfully attacked and routed from the field by General Thomas’s careful planning and tactical misdirection. The Confederate Army of Tennessee ceased to exist as a threat to Union armies (although some of its units were cobbled together under Joseph Johnston to harass Sherman in the Carolinas), leaving Lee’s besieged force as the Confederacy’s last effective field army. Even though Union armies had gained little territory in 1864, Lincoln’s strategy had decided the outcome. In January 1865, Mary Chesnut wrote, “The end had come. The means of resistance could not be found.”30

The end came quickly once the spring weather allowed campaigning in Virginia. Although Lee’s army remained intact, it was worn down by supply shortages, desertions (especially by troops from regions threatened by Sherman’s raids), and political alienation. Grant moved a portion of his army west of Petersburg, cutting its rail connections and threatening to isolate the Army of Northern Virginia from its sources of supply to the south and west. Lee would not be caught in such a trap and maneuvered to escape west. Plagued by supply problems, he was finally stopped by Union forces at Appomattox Court House. Faced with having to attack a prepared Union position, Lee decided to avoid further bloodshed and surrendered on April 9. A week later, Johnston surrendered the other Confederate forces to Sherman. Although there were still thousands of Confederates under arms who could have resisted almost indefinitely as guerrillas, the will to fight on was gone, and the war ended.31

While it would have been possible for Confederate forces to continue fighting, hostilities ceased except for some isolated groups. Armies were still in the field, but the marginal cost of war was far beyond any possible benefit. Lincoln’s liberal terms for readmission of the Southern states into the Union, initially maintained by Andrew Johnson after Lincoln’s assassination, also facilitated the transition to peace. Lincoln’s economic policies had contributed to the Union victory by creating shortages that squeezed the South’s ruling class, but his Reconstruction plan did not include measures to build the economy beyond unsuccessful efforts to provide agricultural opportunities to former slaves. Lincoln’s second inaugural address summarized his approach to putting the country back together: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” Whatever the shortcomings of Reconstruction, Lincoln’s policy created the political space to solidify peace.

The Union had victory, forcing the Confederacy to abandon all its war aims. It accomplished this goal despite the South holding the advantage of strategic defense, having parity of military leadership, and needing not total victory, but merely to maintain resistance until the other side tired. In 1958, with the war’s centennial approaching, Gettysburg College sponsored a conference on why the North won. The findings were later published as a series of essays, each of which examined one factor: political, military, economic, and diplomatic. While the authors noted that there was no one explanation and that advantages in each of these categories contributed to victory, none of the contributors took the next step to consider these elements as essential parts of an overall strategy that won the war.32 Without any one component, the result might have been different. In 1862, for example, the Union tried to employ superior numbers and economic strength, but such commanders as General George McClellan squandered its advantages. McClellan continually demanded more troops of Lincoln, without solid plans for how they would be employed to achieve his goals of defeating Lee’s army and capturing Richmond. His assumption was that reaching these goals would be sufficient to end the war, but the South in 1862 survived battlefield losses and still had plenty of will to fight on.

Clausewitz as Civil War Strategist

If war, as Clausewitz famously wrote, is policy by other means, then successful war requires a clear policy objective combined with the means to achieve it. By eventually coordinating military operations with political, economic, diplomatic, and other efforts, the Union leadership was able to develop a set of policies that gave it a decisive strategic advantage. The Union strategy addressed all three of Clausewitz’s “trinity” of bases for a state to maintain a war effort—the army, government, and people—while wrecking the Confederacy’s passion, creativity, and reason—the Prussian theorist’s “first trinity” of motivations for a people at war. After inflicting losses on Confederate armies, demonstrating the government’s inability to control its territory and increasing the costs of continued resistance to the Southern people, Lincoln created the conditions for victory.

The Confederacy did not arrive at a comprehensive strategy. Davis and Lee correctly identified a strategic goal: eroding Union morale so that Lincoln would lose the election. The Southern leadership did not, however, support this goal with the necessary means to achieve its end. The Confederacy depended almost exclusively on its field armies winning battles to prove the war unwinnable for the North. Lee, in particular, proved effective on the tactical and operational levels, and the Davis administration managed to provide the materiel to keep its forces in the field. These successes, however, were not matched in the political and economic dimensions. The effects of this shortcoming were felt increasingly as the war continued; economic hardship and increasing disunity over the future of slavery took their toll on the South’s will to continue.

Almost as soon as the war ended, analysis of it began. Many in the South tried to pinpoint why they had lost a war they believed had been winnable. In the North, it was easy to attribute victory to the moral superiority of the Union. For ex-Confederates, things were more complicated. The South had fought hard for 4 years, and many had come to dismiss slavery as the reason for the long struggle, focusing instead on self-defense.33 While many agreed with Lee’s assertion that numbers and resources weighed against the South, others looked elsewhere for explanations. Confederate General Pierre G.T. Beauregard wrote that “no people ever warred for independence with more relative advantages.”34 Others, such as Joseph Johnston and James Longstreet, pointed to supposed inadequacies of Davis’s political leadership or that of state governments that put local needs above those of the Confederacy.

By the end of the 19th century, however, most accounts of the war had moved toward the population-resources theory, what historian Richard Current referred to as “God and the heaviest battalions.”35 A 1908 textbook explained that “the North must finally win, if the struggle went on, for its resources were varied and practically unlimited.”36 During the postwar era, the most important national objective was to reconcile the two sections of the country after 4 years of destruction. With reunification taking priority over social justice, the elements of segregation and institutionalized racism developed as long as secession remained off the table.37 Similarly, the idea that the Confederacy had fought the good fight in its own defense and was overwhelmed despite superior military leaders became part of the standard narrative of American history. A textbook published in 1916 reduced the war to a summary of battles and generals, with no mention of overall strategy.38 In the 20th century, historians produced shelves full of books on the Civil War, with most taking a more nuanced look at its outcome. British military theorist B.H. Liddell Hart blamed Lee’s aggressive tactics for eroding Confederate military strength and lauded Sherman’s “indirect approach.”39 Others, such as Frank Owsley in 1925, blamed the doctrine of states rights for undermining Confederate unity.40 None of this work, however, was able to shake the hold of the “overwhelming resources” explanation. In January 2014, in an Internet search of “Why did the Union win the Civil War,” over 90 percent of the hits were some variation of the inevitability of Northern victory by superior numbers.41

Lessons Learned

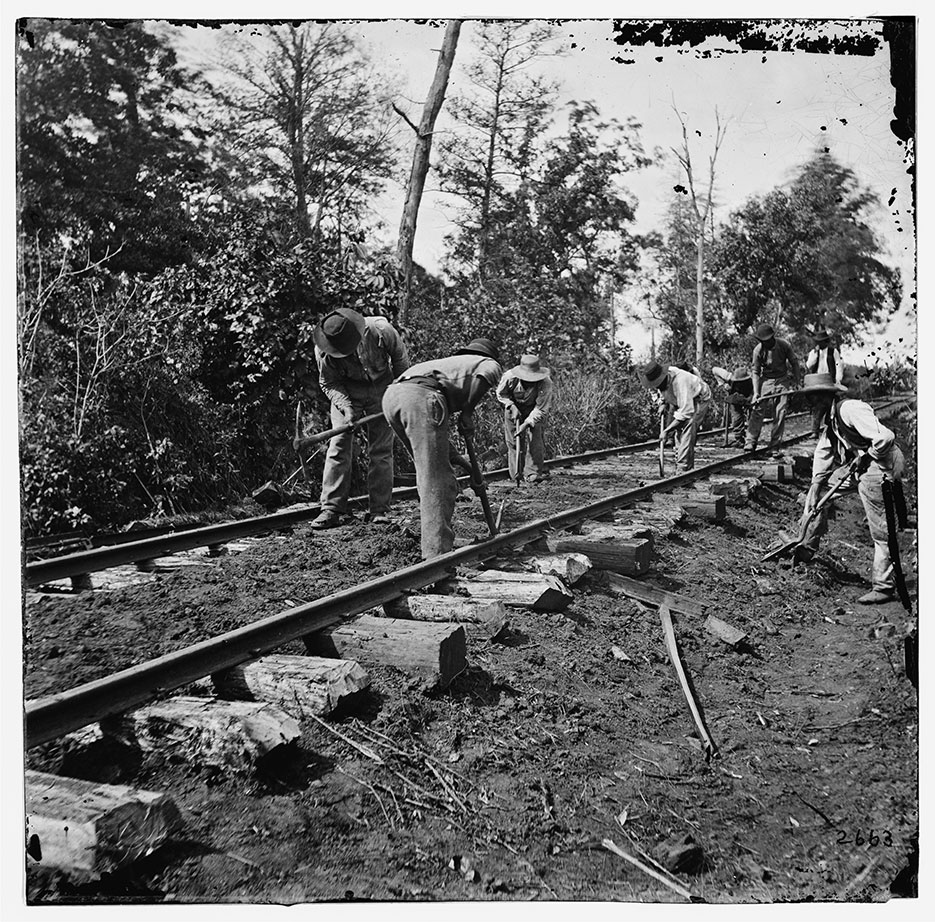

Men repairing single-track railroad near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, after Battle of Stone’s River (LOC)

Since the Civil War, the United States has employed a variety of strategies in military conflicts, but in all of them has sought to apply advantages of size and productive capacity. In World War I, the overall strategy of attrition was set by Allies, and the U.S. contribution was generally perceived as supplying military mass. Recent scholarship, however, has taken a more positive view of U.S. performance in the 1918 offensives.42 It was the presence of large U.S. forces on the battlefield that provided political weight to Woodrow Wilson at the peace negotiations, influence he chose to use to push for a League of Nations rather than an equitable settlement in Western Europe.43 U.S. strategy during World War II again combined diplomatic, political, and economic elements with military operations. U.S. assistance, for example, was important to keeping the Soviet Union in the war and maintaining the strength of the Alliance while U.S. forces built up for the invasion of Europe. U.S. Navy submarine operations played a key role in degrading the Japanese economy by cutting off its supplies of raw materials. Much as with the Civil War, however, many popular accounts of the war focused on industrial production as a deciding factor. NBC television’s influential documentary Victory at Sea devoted most of an episode to the way the United States was able to pour resources into the fight. Similarly, the country succeeded in the Cold War by implementing a comprehensive strategy of containment, first articulated by George Kennan in 1947, which employed all elements of state power to promote “either the break-up or gradual mellowing of Soviet power.”44 In 2011, however, New York Times writer Leslie Gelb assigned credit for the Cold War’s conclusion to the strength and productivity of the U.S. economy.

In Vietnam, the United States faced a situation in which its ally, the South Vietnamese government, could not function effectively. As the war went on, the United States came to rely increasingly on massive firepower to achieve success on the battlefield without accompanying political and economic elements. While the primary reasons for the overreliance on military power were undoubtedly domestic political concerns, by the 1960s, Americans had become accustomed to the idea that superior numbers and resources could win wars. Vietnam prompted many reviews of such assumptions, so that in the 1991 war against Iraq, the George H.W. Bush administration combined its huge advantage in military technology with a diplomatic campaign to build a coalition, economic sanctions, and effective public messaging to ensure success. In 2003, the use of superior force was repeated, but without a suitable strategy to transition from military success to a sustainable peace.

More recently, the importance of strategy has been reinforced. President George W. Bush intended the 2007 “surge” in U.S. troops in Iraq to provide security and allow time for political development. The White House coordinated its plan with Iraqi government policies and the political and economic strategy of the U.S. Embassy. The administration of Barack Obama then attempted to duplicate the strategy’s apparent success with a surge of its own in Afghanistan in 2010. Press coverage of the decisionmaking process in 2010 focused almost exclusively on the issue of troop numbers and whether U.S. Commander General Stanley McChrystal would receive the reinforcement he demanded—a situation reminiscent of General George McClellan’s demands of Lincoln in 1862.45 As of early 2014, despite some success against the Taliban, the overall violence remains unabated, and the Afghan government still shows little evidence of providing for its own security. This development leads to the question: did the surge become an end in itself rather than an instrument of a broader strategy?

Strategy matters. By matching military objectives to political, diplomatic, and economic policies, Lincoln and Grant were able to overcome the Confederate defensive advantages that had stymied the Union for over 2 years. While the Lincoln administration never put together a strategy document like the 21st-century National Security Council does, all of the elements that would go into a modern strategy were present. By combining the policies of the civilian government with military operations, the Union affected the true center of gravity of the Confederacy: the will of its people to resist. Just as the post–Goldwater-Nichols U.S. military used joint forces to increase military effectiveness, the coordination of policies provided a significant force multiplier. From the Mexican War on, advantages in population, resources, and production have been among the most important tools for American success in conflicts. The United States has experienced problems when it relies too much on this set of tools without employing them in the context of a comprehensive policy, and the example of the Civil War can apply to policymakers of the 21st century. Abraham Lincoln stated, “Human nature will not change. In any future great national trial, compared with the men of this, we shall have as weak and as strong, as silly and as wise, as bad and as good. Let us therefore study the incidents in this as philosophy to learn wisdom from.” From the Union victory, Lincoln might have advised posterity of the vital importance of being strategic. JFQ

Notes

- Robert E. Lee, “Farewell Letter to the Army of Northern Virginia,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. IV, ed. Robert Johnson and Clarence Buel (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1956), 747.

- Richard E. Beringer et al., Why the South Lost the Civil War, reprint ed. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991), 424.

- For extensive discussions of each of these factors, see David Herbert Donald, ed., Why the North Won the Civil War (New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1960), for a collection of essays highlighting the various arguments.

- Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones, How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 490–491.

- “The Future Military Policy,” New York Times, February 3, 1864.

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Peter Paret and Michael Howard (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 358.

- Archer Jones, Civil War Command and Strategy: The Process of Victory and Defeat (New York: Free Press, 1992), 158.

- Donald Stoker, The Grand Design: Strategy and the U.S. Civil War (Cary, NC: Oxford University Press, 2012), 352.

- Hattaway and Jones, 312.

- Jones, 235.

- Benson Bobrick, Master of War: The Life of General George H. Thomas (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009), 289.

- Beringer et al., 215.

- It can be argued that the American Revolution and War of 1812 were fought between democratic opponents, but democracy at the time, particularly in Britain, was rudimentary. The British system of the time was a still-developing constitutional monarchy. Had it been truly democratic, the British public likely would have tired of the war long before King George and the Tory government.

- Jones, 184.

- Beringer et al., 307.

- Ibid., 201.

- Ibid., 11.

- Donald, 57.

- Harold Holzer and Craig Symonds, eds., The New York Times the Complete Civil War 1861–1865 (New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2010), 334–335.

- Hattaway and Jones, 571.

- Ibid., 570.

- Ibid., 558.

- Bruce Catton, This Hallowed Ground (New York: Pocket Books, 1961), 405.

- Hattaway and Jones, 593.

- “Atlanta Campaign,” The New Georgia Encyclopedia, available at <www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/atlanta-campaign>.

- Mary Chesnut, Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, ed. C. Vann Woodward (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 642, 645.

- Hattaway and Jones, 640.

- Beringer et al., 380.

- Ibid., 425.

- Chesnut, 704.

- Beringer et al., 345, 403.

- Donald.

- See Beringer et al., chapters 15 and 17. The authors argue that the shift in Southern thinking began during the war as a way to keep its forces motivated, then was solidified by postwar myth-making, focused on “The Lost Cause.” With a consensus emerging that slavery had been morally wrong, Southern apologists chose to focus on self-defense as the reason for their resistance.

- For a commentary on the reason for Southern defeat, see Beringer et al., 425–443. The authors draw a parallel with the performance of Paraguay in the War of the Triple Alliance (1865–1871). The Paraguayans, though facing much greater odds in terms of population, economy, and resources (some Paraguayan units were armed with pikes), were able to resist for a longer period by using the advantages of strategic defense. Their enemies, Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay, relied largely on their numbers to overwhelm Paraguay.

- Donald, 32.

- Andrew Cunningham McLaughlin, A History of the American Nation (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1908), 467.

- Beringer et al., 412.

- Samuel Eagle Forman, First Lessons in American History (New York: The Century Co., 1916), 286.

- Donald, 52.

- Beringer et al., 6.

- A sample of the common views on the question can be found in “Why the South Lost the Civil War,” available at <www.historynet.com/why-the-south-lost-the-civil-war-cover-page-february-99-american-history-feature.htm>.

- See, for example, John Mosier, The Myth of the Great War (New York: HarperCollins, 2001).

- Thomas A. Bailey, A Diplomatic History of the American People (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1980), 605.

- John Lewis Gaddis, George F. Kennan: An American Life (New York: Penguin Books, 2011), 261.

- “The Obama Administration and the War in Afghanistan, 2009–2012,” in For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States from 1607 to 2012, ed. Allan R. Millet, Peter Maslowski, and William B. Feis (New York: The Free Press, 2012), 672.

Âåðíóòüñÿ íàçàä