Журнальный клуб Интелрос » Joint Force Quarterly » №77, 2015

Hurricane Katrina revealed our nation’s lack of preparedness to respond to a complex catastrophe in a rapid, efficient, and effective manner.1 This catastrophe forced a reevaluation of how we plan for and respond to natural disasters and/or emergencies. Over the last 10 years, efforts have focused on new response frameworks and building capacity to respond to such events, but little consideration has been given to capitalizing on a process that would rapidly generate and deploy Title 10 Department of Defense (DOD) capabilities, especially the Reserve components. DOD needs to revise processes in the Adaptive Planning and Execution System (APEX) to recognize and capitalize on the inherent advantage of using Reserve forces in closest proximity to incidents. The current process is cumbersome, inefficient, and potentially leads to unnecessary loss of life and human suffering. History has illustrated over and over again that the first 72 hours of any catastrophe is the window in which we are most likely to save lives. Squandering time to run mobilization of Reserve units through the current force generation process is unacceptable.

Airman refuels F-15 Eagle aircraft attached to 125th Fighter Wing during exercise Vigilant Shield 15 (U.S. Air Force/Brandon Shapiro)

The National Guard (NG), constitutionally under the command and control of the governors of the states and territories, has a primary role to support civilian authorities in the aftermath of emergencies and disasters. The NG has always been the most responsive military asset aligned to perform this role due to the close proximity of the units situated in more than 3,000 communities throughout the Nation. In 2012, Congress wisely expanded community-sourced capabilities with a change to Title 10 U.S. Code (USC) § 12304(a) contained in the 2012 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).2 Today, governors finally have the means to access the Reserve components of the military Services to support a response under The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, as Amended.3

Katrina clearly illustrated that the Active component (AC) and, more important, the NG can rapidly muster and deploy tens of thousands of personnel with a vast array of capabilities, often within the first 12 to 72 hours. The Reserves of the Army, Marines, Navy, and Air Force were not included as part of response efforts for Hurricane Katrina. While accessing the Reserves is a reality today, DOD’s sourcing process is cumbersome and has not captured the intent of the 2012 NDAA in which Congress recognized the responsiveness of the Reserves for these types of events. Like the NG, the Reserves are located in communities throughout the country.

Furthering the knowledge captured from lessons learned with Hurricane Katrina, National Level Exercise 2011 studied a complex catastrophe along the New Madrid Fault involving a future multistate earthquake in the Midwest. The after-action report revealed that a response to a 7.7 magnitude earthquake was likely complicated due to numerous cascading effects outside the zone of impact. The predicted Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) required is expected to be on a scale not seen in any previous disasters/catastrophes.4 It is well known that state and local governments cannot afford to fund significant contingency capabilities; they rely on mutual aid agreements, compacts, and mutually supportive response frameworks to come to each other’s aid when local incident response resources are exhausted. When we compare state and local contingency capacity to that of the entire U.S. defense establishment, it is clear that the defense establishment’s depth is unmatched and specifically funded to train for and execute contingency operations in either a homeland defense or homeland security role (up to and including response to emergencies, disasters, and complex catastrophes).

The states have the primary responsibility both for homeland security and for response to emergencies, disasters, and complex catastrophes. A key legal exception to this is codified under the Insurrection Act of 1807, which grants the President special powers relating to a state’s inability to enforce its own and Federal law. The U.S. Constitution established the rights of the people and delineated the rights and responsibilities between the several states and the Federal Government. The Preamble to the Constitution states, “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.”5

The Constitution affirms common (homeland) defense as a primary Federal responsibility:6 The “United States . . . shall protect each [state] of them against invasion; and . . . against domestic violence.”7 The term domestic violence relates to powers granted to the President under the Insurrection Act.8 The Second Amendment recognizes the rights of the several states to form and have “a well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State,”9 and the Tenth Amendment provides that “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”10 These key provisions place primary responsibility for homeland security and the general welfare of the people with the states and territories, and defense of the homeland with the Federal Government, specifically, the Department of Defense. Governors inherently are the heads of state and therefore are ultimately responsible for the security and general welfare of the people in their geographic jurisdictions. The importance of the Constitution in this discussion is that all disasters are state matters; therefore, state and local governments, when able to act in this capacity, are always in charge of their response. The Federal Government solely supports these efforts.

The Stafford Act provides the legal authority for the Federal Government, including DOD, to provide assistance to the states in cases of emergencies or natural and other disasters outside of Immediate Response Authority (IRA).11 Under the Stafford Act, the President is delegated emergency powers and may declare an event a major disaster or emergency. Generally, Stafford Act assistance is provided upon request of a governor, provided certain conditions are met: primarily, the governor must certify that the state lacks the resources and capabilities to manage the disaster or emergency. The Stafford Act allows the President, on his own authority, “to declare an emergency, but not a major disaster . . . with respect to an emergency that ‘involves a subject area for which, under the Constitution or laws of the United States, the United States exercises exclusive or preeminent responsibility and authority.’”12 “A prime example of preeminent federal authority . . . lies in the realm of homeland defense.”13 For a detailed discussion of the roles of the states and the Federal Government under the Stafford Act, please read the Domestic Operational Law Handbook.14

Federal civil authorities supported by DOD respond to simulated 6.0 magnitude earthquake on New Madrid Fault Line as part of National Level Exercise 2011 (U.S. Air Force/Maxwell Rechel)

Hurricane Katrina marked a new era for the emergency management field and gave birth to a whole host of efforts in developing revised strategies, new frameworks, and plans, and was a precursor to the DOD concept of a complex catastrophe.15 A 2006 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report to Congress revealed that key failures in responding to Katrina were from a lack of a framework outlining leadership roles, responsibilities, and lines of authority at all levels, and the failure to clearly define and communicate the same to facilitate rapid and effective decisionmaking.16 The report also highlighted the lack of detailed plans needed to delineate capabilities that might be required, and how to provide and coordinate such assistance.17 Prior to Katrina, the typical Federal posture was to wait for the affected states to request assistance.18 Katrina illustrated how the NG and AC could muster tens of thousands of personnel with a vast array of capabilities within the first 72 hours.

In response to Hurricane Katrina, 54,000 NG and 20,000 Title 10 personnel were deployed to the Gulf Coast under separate chains of command.19 The difficulties in integrating Servicemembers under separate chains led President George W. Bush to ask the governors of the three states involved to appoint Lieutenant General Russel L. Honoré as a dual-status commander and place all forces under his command, effectively Federalizing the NG. All three governors refused, including the President’s brother, Governor Jeb Bush of Florida.20

After Katrina, the DOD solution was to have command and control over all military forces in domestic (and, in particular, multistate) emergencies, including NG forces.21 DOD proposed legislation that became part of the 2007 NDAA. The 2007 NDAA amended the Insurrection Act of 1807, which for 1 year allowed the President, without the prior knowledge or consent of the governors, “to federalize the National Guard and mobilize all other military components to respond to ‘any serious emergency.’”22

In reaction to this in 2007, the Commission on the National Guard and the Reserves and the Council of State Governments called for the repeal of the changes to the Insurrection Act, which was accomplished in the 2008 NDAA.23 DOD proposed similar legislation in 2009 and 2010 that did not pass.24 In 2010, President Barack Obama established the Council of Governors (COG) by executive order.25 In consultation with DOD, the COG developed the Joint Action Plan for “Developing Unity of Effort.”26 The Joint Action Plan provides that:

the Governor of the State affected will normally be the principal civil authority supported by the primary federal agency and its supporting entities and the Adjutant General of the State or his/her subordinate designee will be the principal military authority supported by a duly appointed Dual-Status commander acting in his or her State capacity.

In the 2012 NDAA, Congress incorporated these principles into Federal law.27

The 2012 NDAA also expanded Federal assistance under the Stafford Act by providing the Secretary of Defense the authority to order members of the Reserves to Active duty for up to 120 days “to respond to the Governor’s request.”28

Water purification specialist, part of unit deployed into Rockaway, New York, in direct support of FEMA, state, and local officials, channels water away from housing complex after Hurricane Sandy (U.S. Army/John Adams)

Currently, the Office of the Secretary of Defense’s 2012 Guidance for Employment of the Force only recognizes the primacy of the NG of the states and territories, acting under state control, to provide initial response forces for natural or manmade catastrophes with the only prime exception related to the chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosives response enterprise.

The 2013 Strategy for Homeland Defense and Defense Support of Civil Authorities highlighted that “defending U.S. territory and the people of the United States is the highest priority of the Department of Defense, and providing appropriate defense support of civil authorities is one of DOD’s primary missions.”29 Part of this strategy recognizes leveraging IRA,30 geographic proximate force sourcing, and ready access to non–National Guard Reserve forces.31 While this groundbreaking strategy offers a proper focus to the topic, little if any changes were offered in the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review32 and the DOD fiscal year 2015 budget request33 to ensure this reality is achieved; this highlights the disconnect between current strategy and policy.

Historically, when preparing for disasters, state emergency management agencies (EMAs) and the states’ National Guard units work with local partners to network, establish relationships within the National Response Framework, and develop all hazard response plans maximizing mutual aid between civilian agencies and the NG. In addition, many states have operation plans to respond to known potential catastrophes along key terrain. Today, the rest of DOD is largely not engaged in these discussions at the state and local levels with exception to the Defense Coordinating Elements located in each of the 10 Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) regions.34

Where capabilities exceed capacity, planned or not, local mutual aid agreements and state-to-state Emergency Management Assistance Compacts (EMACs) have been the typical means to fill shortfalls. When they are not adequate in terms of capabilities or time available to employ them, requests for Federal assistance are made. State National Guards primarily receive mission assignments from their respective state EMAs. These mission assignments can be under Title 32 under IRA or, if requested outside of IRA, under state Active duty or Title 32 § 502(f) if authorized by the Secretary of Defense under a Stafford Act declaration.35

For a state to secure Title 32 forces located outside its borders, state-to-state EMAC requests for NG forces have been the typical arrangement to obtain needed military capabilities. Outside of IRA, Title 10 forces are typically deployed only after the President declares a Federal emergency or disaster under the Stafford Act or Insurrection Act.

When a state governor requests a Federal capability, FEMA, under the Department of Homeland Security, becomes the lead agency for managing such requests under a Federal response declared under the Stafford Act. With a Stafford Act declaration, FEMA will typically establish a joint field office (JFO) comprised of a state coordinating officer, Federal coordinating officer, and Defense coordinating officer (DCO), along with their supporting staffs.

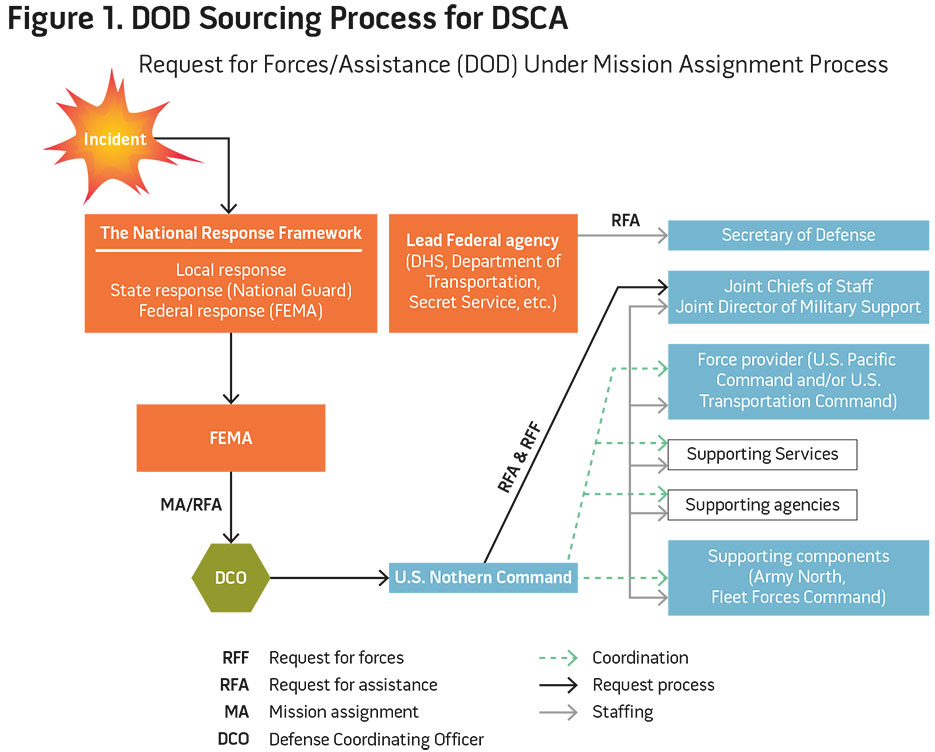

Predicated that all state assets are exhausted, including the state’s National Guard, the state EMA will generate a mission request for a capability and then either pass it to another state under EMAC or send it to the JFO to source the capability from assets nested in the Federal Government. If the request is determined to be a Title 10 solution, the DCO validates the request and forwards it to U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) for sourcing and generation using the Joint Operation Planning and Execution System (JOPES) as outlined in figure 1.36

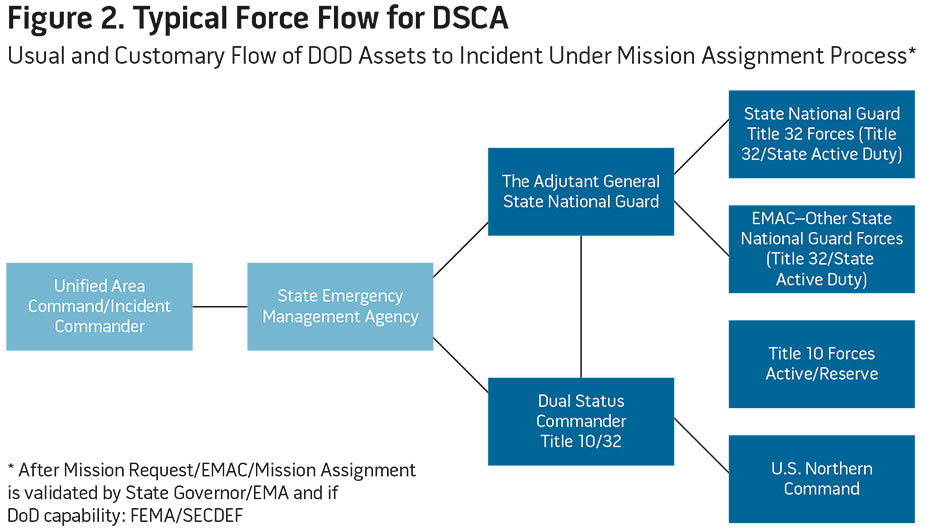

The Title 10 capability, once approved by the Secretary of Defense, deploys and comes uner the operational control of USNORTHCOM. The usual and customary command and control arrangement in support of civil authorities, including major disasters and emergencies, is through the establishment of a dual-status commander (a National Guard officer of the state) trained and qualified by the USNORTHCOM commander. The governor of the affected state will request that the President approve the activation of a dual-status commander.37 The USNORTHCOM commander will assign the dual-status commander either operational or tactical control of Title 10 forces.

The process for generating and deploying Title 10 forces under this current system is not as responsive as the one used by the NG; JOPES was largely designed to handle defense of the homeland and to fight the Nation’s wars. The NG excels at rolling out the door at a moment’s notice at the governor’s request in large part because they live within 50 miles of the units they serve and the process for employment is streamlined.

Congress recognized the same inherent potential with the Reserves when Congress changed 10 USC § 12304(a) in the 2012 NDAA; clearly Congress envisioned the Reserves of the military Services as having the ability to be equally responsive as the NG.

There has been much discussion on this topic. In discussion with many of the DCOs, there is an overriding concern that the Reserves are too expensive and the AC is more cost effective because pay and allowances are already expensed in the base DOD budget; the only additional cost for AC forces is related to transporting and sustaining the Title 10 force deployed. While this statement is true, it does not take into consideration the importance of generating forces within the first 12 to 72 hours when the greatest opportunity to save lives is probable. Incident commanders focus on solving the problems that confront them and they really do not care about where a capability comes from—they are solely concerned that the capability gets there quickly.

Like the NG, Reserve units are present in every state and in over 3,000 communities across the country. AC Title 10 forces, on the contrary, are more concentrated and geographically constrained, hindering the response time due to proximity necessary to assist with the aftermath of an emergency or catastrophe; APEX for these purposes currently lacks speed and efficiency. The AC also does not dedicate training time or resources to be able to respond under the National Incident Management System.38

In contrast, state NGs are much more responsive to another state’s requests for assistance under EMAC. Figure 2 highlights the usual and customary flow that military capabilities can expect to follow once issued a mission assignment under an EMAC or request emanating from the DCO. It is crucial to recognize that the NG construct involves two phone calls followed by a written request, whereas the Title 10 request process has to circulate through much of DOD. The Defense Department needs to look at the sourcing process from the incident commander’s perspective. One complicating factor not experienced to date is the resource adjudication process associated with a complex catastrophe as it relates to state-to-state EMACs.39

The Reserves can generate and deploy capabilities from the very communities they live in as rapidly as the NG if DOD changes the current process used to source them. Like the NG, Reserve members are members of the communities and states in which they live and have the opportunity to be integrated in the response plans of the state’s EMAs. They also have an inherent care for the citizens in the states they serve in. Hurricane Sandy illustrated the seamless integration of all military components in their response under a dual-status commander construct. The only difference was Sandy was forecasted days before it occurred. What would happen with a truly no-notice event like a catastrophe (for example, an earthquake) along the New Madrid Fault?

DOD needs to attack this problem from three fronts. One, direct the commanders of the Reserve components to have their subordinate commands establish relationships with the state EMAs and NGs in the states in which their units reside; assign all units a core mission assignment in line with the NG Core 10 capabilities as outlined in National Guard Regulation 500-1.40 Two, the DCOs working in conjunction with USNORTHCOM should track and monitor Active and Reserve unit capabilities and readiness cycles to know which units are ready to deploy rapidly at the request of a governor. It is acknowledged that individual Servicemember readiness standards for fitness for duty will drive deployment of any individual but that should not stop the entire unit from deploying. Three, DOD needs to establish new policies and regulations to address sourcing of Reserve assets and consider delegating force generation to the commander of USNORTHCOM, executing mobilization in conjunction with the Services and DCOs.

Deputy Secretary of Defense addresses attendees during APEX Senior Executive Orientation Program designed to provide joint orientation for new executives in DOD (DOD/Adrian Cadiz)

DOD has not implemented a process to exploit the use of the Reserves in response to requests from a governor for support under the Stafford Act nor has it embraced the 2013Strategy for Homeland Defense and Defense Support of Civil Authorities. The Defense Department needs to fully adopt this 2013 strategy through revision of the Guidance for Employment of the Force, policies relating to DSCA, and processes to generate and deploy forces under the Stafford Act. U.S. citizens see our military through one lens and are only interested that their military arrives ready to assist in a rapid, efficient, and coordinated manner in a time of need. JFQ