Журнальный клуб Интелрос » Joint Force Quarterly » №81, 2016

Lieutenant Colonel Ross F. Lightsey, USA, is a Special Forces and Civil Affairs Officer assigned to the Joint Planning Support Element within the Joint Enabling Capabilities Command. Previously he was the Joint Force Command J9 during Operation United Assistance in Liberia.

Our daily contact with key Liberian government ministries helped us to understand the government’s plan to contain the Ebola virus, and enabled us to develop critical relationships in keeping lines of communication open, which allowed us to apply resources at the right place at the right time to fully support their plan.

An old fable tells that a single stick by itself is weak; bundled with others, however, the stick will be much stronger. Likewise, during the world’s 2014–2015 response to the Ebola crisis in Liberia, interagency, intergovernmental, and international forces were strong and firmly united, moving forward with a singular agenda. If, on the other hand, all 100-plus organizations had not been united by the Liberian government to stamp out Ebola, the effort would have been weak and ineffective.

Airman assists healthcare worker in donning personal protective equipment to work in Ebola treatment unit (U.S. Army/V. Michelle Woods)

Many organizations, institutions, teams, and individuals came to assist Liberia in stopping the spread of Ebola, as the Liberian government took the lead in harnessing resources and funding, corralling numerous aid workers, and providing leadership in the implementation of a strategic healthcare plan. The Liberian government accomplished this through a unifying process that was labeled the Incident Management System, which was a clearinghouse of meetings and decisions made at the National Ebola Command Center (NECC).1 Having shared equities, the joint, interagency, intergovernmental, multinational (JIIM); nongovernmental organization (NGO); and economic communities came together and became a true force.

On September 16, 2014, President Barack Obama conveyed four goals to combat Ebola:

The goal of coordinating a broader response later included providing unified and coherent leadership by having the U.S. interagency community and military support the efforts of the Liberian government. With that said, the collaborative atmosphere lent significant confidence to the international community in the competence of the unified partners who were tackling the tasks at hand. The American people needed this confidence with a unified leadership as the fears of Ebola were rapidly growing in the fall of 2014.

The deployment of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) headquarters and applicable units, with 2,692 Soldiers at peak manning in both Liberia and Senegal, formed Joint Force Command–United Assistance (JFC-UA), which supported the Liberian government and the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID’s) Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) and, more specifically, a USAID/OFDA Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART). JFC-UA was tasked to:

The end result was a greatly diminished Ebola transmission rate in Liberia.

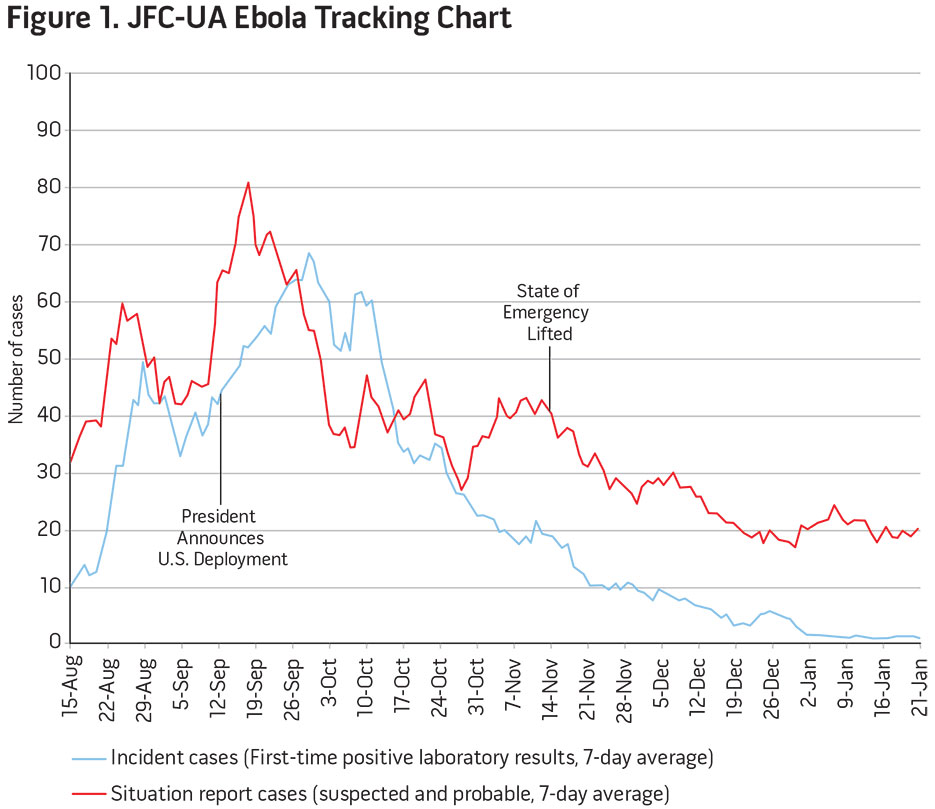

Upon the arrival of U.S. troops in Liberia in September 2014, the rates of Ebola infections were approximately 367 new cases per week; upon their departure in March 2015, however, new cases were less than 2 per week (see figure 1). In short, JFC-UA in support of USAID efforts, coupled with other U.S. interagency partners and the international community writ large, banded together to focus on one task: eliminate Ebola in Liberia.

Understanding Ebola and Military Application Background

The word Ebola is derived from the Ebola River Valley in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the initial 1976 outbreak of the disease occurred.3 It has existed for decades but has been generally contained with varying degrees of success in other African regions. In humans, Ebola is typically spread through bodily fluids, similar to HIV. Although Ebola is not an airborne disease, it has a high rate of transmission among humans, especially with physical contact of dead tissue or person-to-person contact (transmittable only if one has Ebola and is symptomatic and permeating Ebola). Because of the rapid transmission rate and unprecedented outbreak in West Africa, Ebola became a global concern and was deemed a matter of national security by President Obama.

In July 2014, American fears of Ebola were validated when a missionary doctor contracted the disease and was medically evacuated to the United States. In September, the incident at Texas Health Presbyterian hospital in Dallas increased concern as a nurse contracted the disease while treating Thomas Eric Duncan, a Liberian who was the first to be diagnosed with Ebola in the United States. Fear in the American populace caused the President to act decisively and quickly.

The U.S. Response

In his September 2014 speech, President Obama announced his plan to use 3,000 troops in West Africa to support USAID as the lead Federal agency. He spelled out that the troops would primarily operate in Liberia and would be supported from an air bridge out of Senegal. Immediately, U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM) and U.S. Army Africa (USARAF) began on-ground assessments and also initiated the Joint Operation Planning Process (JOPP) to determine what kind of military capabilities were required, what support mechanisms would be needed, and where to place the troops in respective countries. In all of this, USAFRICOM and USARAF staff worked closely with USAID/OFDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to determine what the tasks were and what Request for Forces would be sent to the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD).

The 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) was chosen to lead the effort by providing a division-level staff to direct and manage various units derived from 16 different installations. The coordination and synchronization in bringing these various entities together were daunting, but were a definite requirement as the specialty fields (such as epidemiologist) do not solely reside within a U.S. Army division headquarters or Brigade Combat Team.

Unique Training

So how do an Army division staff and applicable units train for such a deployment? Of course, the applicable units at their respective U.S. locations conducted mandatory donning and doffing training for protective equipment and some standard predeployment training. Preparation needed more than tactile training, however, as we defaulted to an educational approach in learning about Ebola itself, the culture and leadership of Liberia, and our operational environment (including our JIIM partners). We also reached out to interagency partners (USAID and CDC), as well as various international governmental organizations (United Nations [UN] Mission for the Ebola Emergency Response and World Health Organization).

To educate the command and staff, a 2-day Interagency Academics Seminar was developed by the Mission Command Training Program at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and the division G9. This seminar brought together USAID/OFDA, CDC, Department of State, UN, U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH).

JFC-UA Composition

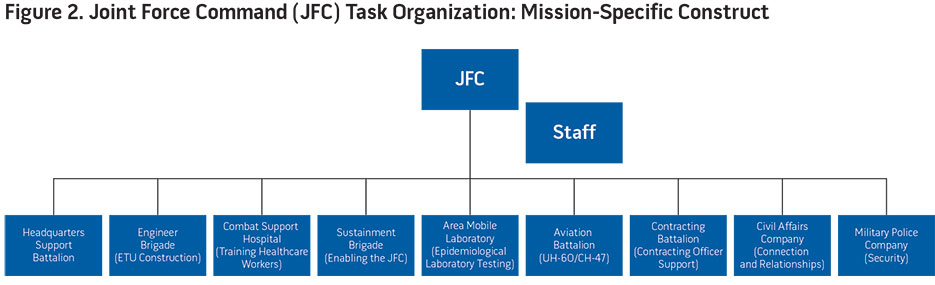

Noted earlier, USAFRICOM and USARAF developed the manning requirements through the JOPP with inputs from USAID/OFDA and CDC. Those involved planned products to tackle Ebola through the training of volunteer healthcare workers, constructed ETUs, sustained military logistical requirements, and assisted the international community with logistical requirements. The task organization was developed by function or enabling support (see figure 2).

Liberia: An American Extension

One of the best explanations for rapid success in Liberia was working with a supportive government that has close ties with the United States and other Western nations. A considerable portion of the Liberian leadership is Western educated, and its military receives training in the United States. For example, the primary driver in the Liberian Ministry of Health (MoH) was educated at The Johns Hopkins University, and a senior commander within the armed forces of Liberia is a 2012 graduate from the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth.

Liberia is primarily an English-speaking country, predominantly Christian, has a similar governing constitution and democratic process (executive, legislative, and judicial branches), and retains many American cultural norms due to its historical ties with the United States. These close ties date back to the antebellum years when freed slaves from the United States established Liberia.4 As a result, U.S. efforts were well received, making communication, coordination, and collaboration more fluid.

Working in a permissive environment and operating with a supportive indigenous populace, U.S. preparation for language and cultural training in a standard contingency premission training model was nearly moot. This environment was unique in that the U.S. military directly supported the USAID/OFDA DART. Working together, both the DART and JFC-UA coordinated all operations in Liberia through the U.S. Ambassador in Monrovia.

JFC-UA reported to USAFRICOM for military-related tasks and management of Ebola resourcing through the overseas humanitarian, disaster, and civic aid lines of accounting. Furthermore, logistical support, budgeting allocation, military orders, transportation, and other military operations were coordinated through USAFRICOM.

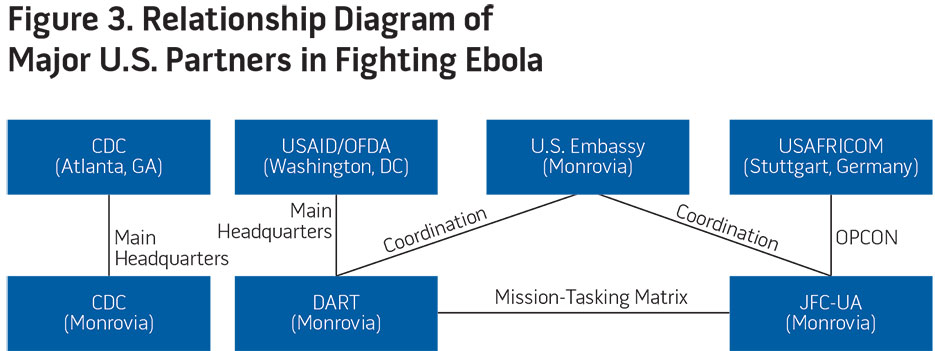

USAID/OFDA operated on the ground via the DART, which was responsible for coordinating the interagency response, assessing the situation, and identifying gaps in response efforts. The DART was comprised of staff from various U.S. agencies, including USAID/OFDA, CDC, and HHS (see figure 3). USAID used the Mission Tasking Matrix (MITAM), a mechanism used to request operations from the DART to JFC-UA. It was developed by USAID and is a standard procedure for validating, prioritizing, submitting, and tracking requests for Department of Defense (DOD) support during disaster responses. Some of the validated requests were forwarded from the DART Civil-Military Affairs Coordinator/MITAM Manager to the JFC for review and execution at the lowest level, but some of the MITAM requests were from USAID to OSD at higher levels. Regardless, the MITAM process was vetted, validated, and coordinated at the applicable parallel chains of authorities.

Building Civil-Military Relationships

Many questions were asked about how multiple, unrelated entities built such a solid foundation by working together. One answer: do not get fixated on what you are wearing, whether a vest, tie, or military uniform. Rather, focus on solving the problem facing all. Moreover, do not worry about who receives credit in the various tasks at hand, but stay on-task and be passionate about the one common goal—eliminating the threat of Ebola.

In Monrovia, the DART consisted of approximately 20 experienced disaster relief personnel in the Ebola fight, whereas at peak manning, 2,453 personnel were assigned to JFC-UA (“boots on the ground” in Liberia), a huge variance in capacity and capability between the two. So how do we collectively integrate operations with such a huge disproportion in personnel and logistical footprints? First comes communication, then coordination, then ultimately collaboration.

To have communication among these entities, having strong, experienced, and knowledgeable liaison officers (LNOs) is a must. An LNO can assist in staffing requirements and can be a strong strategic voice to speak on a unit’s behalf. The DART had solid civil-military LNOs, as well as JFC-UA, which contributed experienced and competent LNOs that had previous exposure to interagency and U.S. Embassy operations. It is important that the LNOs to be exchanged are able to articulate operations through effective communication as well as expressing the command message.

To ensure transparency, there were some growing pains in communication at the initial onset of the operation. JFC-UA and DART tackled this communication gap by having daily meetings at the Embassy with the command group and Chief of Mission (U.S. Ambassador), semi-weekly interagency synch meetings, and nightly operations-synch meetings with the DART MITAM managers. Furthermore, to reach a consensus in having a common language, an “Ebola synch matrix” was collectively established between DOD elements and the interagency community to assist in mapping the fast-paced construction of the ETUs, training healthcare workers, establishing Army medical test (verifying Ebola samples) labs, and providing DART-directed logistical support via MITAMs to the international community. This Ebola synch matrix of time-to-task mapping put everybody on the same page and gave a greater shared understanding of impending requirements. Indeed, the level of collaboration between units and organizations is directly proportional to interpersonal skills and open-mindedness to new and different people.

Snapshot of Partners

U.S. Interagency Community and DOD. The DART, Embassy, and JFC-UA were not the limit of American cross-organizational exposure; there were numerous other U.S. interagency partners that were brought into the fold. The largest and most knowledgeable institution that the DART and JFC-UA collaborated with was the CDC. CDC epidemiologists and leadership gave specific insight and direction in how to contain Ebola, if not completely eradicate the disease. Moreover, other institutions greatly contributed to the fight in Liberia: U.S. Public Health Service, Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Defense Logistics Agency, Naval Medical Research Center, HHS, USAMRIID, and the NIH. All organizations were tied to one another through LNOs, routine meetings, or other routine dialogue forums. Again, having dedicated communication through physical presence and proximity is key to having a successful collaborative environment.

Intergovernmental Organizations. U.S. involvement in Liberia was only a portion of the total contribution from the international community. For example, the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) has over 6,000 peacekeeping troops and police currently stationed throughout Liberia and has an already existing logistical structure and knowledge of key civic Liberian enablers in the field. There were many other organizations, but most notably the newly established UN Mission for the Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER), whose charter was to have limited authorities over existing organizations in the fight against Ebola through what is termed the UN Cluster System where a unity of effort is pursued within the multiple UN systems.5 “Clusters” are groups of humanitarian organizations (both UN and non-UN) working in the main sectors of humanitarian action—for example, shelter and health. They are created when clear humanitarian needs exist within a sector, there are numerous actors within sectors, and national authorities need coordination support. Obviously, coordination is vital in disaster responses. Good coordination means fewer gaps and overlaps in humanitarian organizations’ work, and coordination ensures a needs-based rather than a capacity-driven response. It aims to ensure a coherent and complementary approach, identifying ways to work together for better collective results.

So accordingly, UNMEER led and managed a Liberia-wide civil-military synchronization effort that included, but was not limited to, JFC-UA civil affairs teams, UNMIL, UN Children’s Fund, World Health Organization, World Food Programme, UN Disaster Assessment and Coordination, UN Development Programme, Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance, UN Humanitarian Air Service, Economic Community of West African States, World Bank, African Union, International Organization for Migration, International Committee of the Red Cross, and African Development Bank.6 The JFC-UA used the special operations force approach of using existing international and indigenous assets and gained benefits of these supporting infrastructures of knowledge through human engagement.

Multinational Efforts. Excluding UNMIL, which had over 45 nations represented, there were a number of independent efforts from various countries. Most prominent to the collective efforts between the DART and JFC-UA was the German NGO Welthungerhilfe, which offered to build four ETUs in southern Liberia through DART assistance and funding. This gesture at the beginning of American involvement lent solid evidence of quickly forming multinational relationships. U.S. forces came en masse starting as early as September 2014 and were quickly followed by the Germans, a Swedish contingent, and a Chinese military delegation—all assisting in the construction and manning of ETUs. Again, having shared equities among the international community, the DART, JFC-UA, and Liberia itself benefited from the informal tight band of this ad hoc coalition.

Host-Nation Organizations and Military. In recent combat experiences, the U.S. military conducted multiple civil-military tasks of support to civil administration, where emerging and newly formed democracies had much room for improvement—and, to be candid, these experiences were an uphill battle.7 However, the Liberian government is extremely competent, educated, and highly organized. The most prominent organization that JFC-UA and DART collaborated with was the Liberian Ministry of Health. On a daily basis JFC-UA and DART sought interaction and communication with the MoH at multiple levels. Furthermore, as social mobilization and psycho-social issues related to spreading the word on the prevention of Ebola, our LNOs attended meetings at the Ministry of Information, Culture, and Tourism.

In addition to the MoH, the government of Liberia relied heavily on its military to help control the outbreak and contain the disease within its borders. Obviously, JFC-UA was the primary interlocutor with the DART and other U.S. organizations as the Liberian military worked closely with JFC-UA to provide security, construct ETUs, and facilitate JFC-UA and DOD operations.

Economic and Commercial Interests. In a JIIM-centric mission, units typically research their PMESII (political, military, economic, social, infrastructure, and information) or ASCOPE (areas, structures, capabilities, organizations, people, and events) analyses throughout planning processes. A deliberate Liberian country study and operational analysis were indeed conducted prior to JFC-UA departure and employment. However, we undervalued the economic aspect in PMESII, as upon arrival we found many commercial investors involved in the fight against Ebola due to profits being adversely affected. Their influence was of notable significance during the initial mass exodus of influential leadership in the summer of 2014 as economic forums began to form. For example, private investors developed the Ebola Private Sector Management Group, where overt information was disseminated and private collaboration between business leaders was initiated.

Another example where private industry proved valuable to the effort was during the initial days of the outbreak. The Firestone Corporation offered JFC-UA partial use of their one-million-acre rubber tree plantation. The facility included its own medical facilities, educational system, security, and essentially its own infrastructural system—all separate from the government of Liberia. Principally, the negative economic impact caused Firestone as well as other corporations (for example, ArcelorMittal, Exxon-Mobile, Severstal mining, Chevron) to have vested interests in tacitly or overtly supporting the Ebola containment effort. With this in mind, do not discount or underestimate the power and influence in the economic industry before, during, or after a humanitarian assistance/disaster relief operation.

Other DOD Agencies. JFC-UA was not the only DOD entity operating within Liberia, as coordination with other institutions was vital. In any joint task force–like system, there may be other DOD entities that are not directly subordinate to the JTF command structure but that will at least have some sort of coordinating responsibility, as efforts will surely need synchronization.

An existing Department of State Partnership Program (Operation Onward Liberty), primarily led by the Michigan National Guard, was a separate effort in assisting the training of the Liberian military that had been ongoing for a number of years. Having this background was fortuitous, as the National Guard’s “Persistent Engagement” with the Liberian military assisted JFC-UA in sustaining rapport through longstanding military-to-military relationships.8

Other DOD efforts in the fight against Ebola included the Defense Logistics Agency, U.S. Transportation Command, and Defense Attaché office resident with the Embassy in Monrovia. There were also nine U.S. military officers assigned to UNMIL. Though they were not directly supporting JFC-UA or Ebola efforts, the UNMIL officers provided excellent connectivity to the 6,000-plus UNMIL force operating in Liberia and coordinated support for JFC-UA.

National Ebola Command Center. Beyond a shadow of a doubt, the center of gravity where collective and collaborative decisions were made was within the NECC, a three-story business building that was converted for a single operations nerve center. Since Liberia is a fully functioning and sovereign state, the Liberian MoH managed the NECC’s functions and led frequent Incident Management System meetings. In addition to these meetings, side meetings regarding nationwide logistical coordination, civil-military coordination meetings, psycho-social mobilization strategy meetings, dead body management, the Ebola hotline, and epidemiological surveillance meetings occurred on a routine basis at this location. It cannot be stressed enough that the NECC was the most central location and source of information and was where major cooperation and decisionmaking occurred. If it had not been developed and implemented by the MoH, the opportunity for organizational collaboration would have been hard pressed for success.

Correlation versus Causality?

If one objectively looks at the Ebola trend chart, there is a direct inverse correlation between the arrival of JFC-UA and the regression of confirmed Ebola contractions. It is easy for various institutions to take credit, but there is not enough scientific analysis to determine the actual catalyst and cause in eradicating Ebola. Perhaps the precipitous drop in Ebola rates in the fall of 2014 may not be directly attributed to the arrival of JFC-UA and the DART, whereas the arrival of thousands of U.S. troops, along with hundreds of epidemiological specialists, provided surety, speed, flexibility, but most importantly confidence in that the international community was serious about assisting Liberia eliminate Ebola.

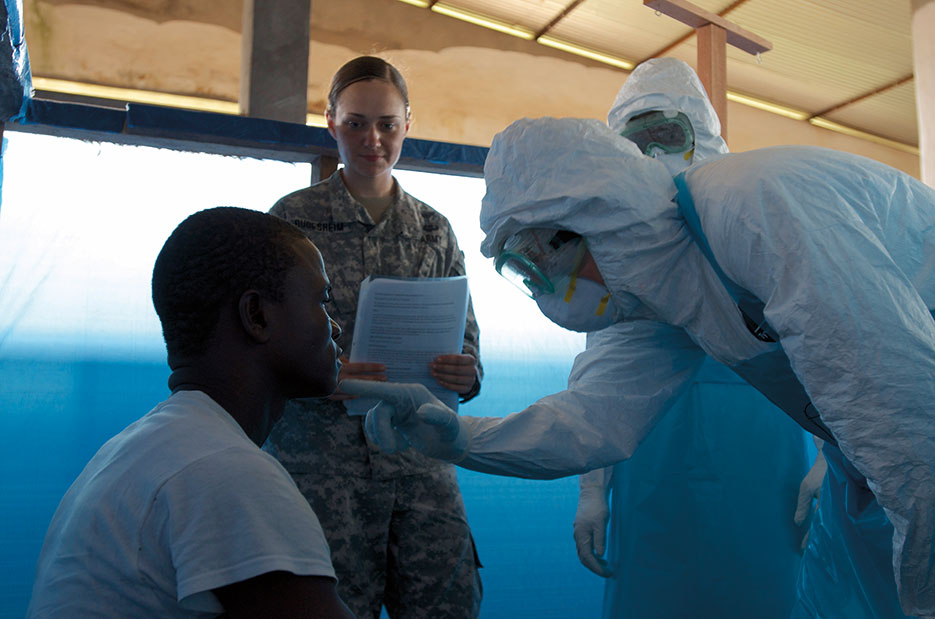

Students in Ebola Treatment Unit Course led by Joint Force Command–United Assistance, diagnose potential patient for symptoms of virus during scenario training, Monrovia, Liberia, November 20, 2014 (U.S. Army/V. Michelle Woods)

We should keep in mind that during the past 15 years, Liberia has had its share of internal strife, and in the summer of 2014 during the mass exodus of expertise, the conditions were ripe for civil disorder. According to a World Bank survey, “Nearly 85 percent report having sold assets, sold or slaughtered livestock, borrowed money, sent children to live with relatives, spent savings, or delayed investments.”9 However, the arrival of over 2,600 U.S. troops, helicopters, trucks, medical personnel, the DART, CDC, and other U.S. interagency efforts collectively conveyed confidence—not only among the Liberian population but also in the international community. The arrival of troops and the DART was a catalyst that brought in other nations, NGOs, international organizations, volunteer healthcare workers, and the return of independent missionary and philanthropic organizations that were previously treating Ebola patients.

As such, the speed of DART and JFC-UA efforts in building the ETUs, training healthcare workers, providing direct funding, and assisting with logistics might have prevented total loss of civil control and order during this tenuous and fragile state of uncertainty. To reaffirm, it would be judicious to caution against attributing direct success related to JFC-UA and the DART, but it would be safe to assume that the arrival of U.S. troops and an overtly collaborative international community played a significant role in the eradication of Ebola in Liberia.

Ebola: Humanitarian Assistance/Disaster Relief, or National Security Threat?

Joint Publication (JP) 1-02, Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, defines foreign humanitarian assistance (FHA) as “activities conducted outside the United States and its territories to directly relieve or reduce human suffering, disease, hunger, or privation.”10 Moreover, JP 1-02 defines foreign disaster reliefas “assistance that can be used immediately to alleviate the suffering of foreign disaster victims that normally includes services and commodities as well as the rescue and evacuation of victims; the provision and transportation of food, water, clothing, medicines, beds, bedding, and temporary shelter; the furnishing of medical equipment, medical and technical personnel; and making repairs to essential services.”11

Because “disease” is mentioned in the definition of foreign humanitarian assistance, doctrinally this mission could be considered an FHA mission, and not necessarily an immediate disaster relief mission from a tsunami per se. However, one could argue that since there was not an immediate human suffering requirement (such as Haiti in 2010), and coupled with the fact that Ebola was becoming an international pandemic (not endemic) threatening the United States, then it would suffice to label this mission as more of a national security health mission from a strategic perspective, as well as humanitarian on an operational level. Consider President Obama’s words: “I directed my team to make this a national security priority. We’re working this across our entire government, which is why today I’m joined by leaders throughout my administration, including from my national security team . . . so this is an epidemic that is not just a threat to regional security—it’s a potential threat to global security.”12

In the summer and fall of 2014, the United States was in near hysteria regarding the threat of Ebola. Both Congress and the President were under pressure to act decisively and to root out the source of Ebola fears. These fears were confirmed and reinforced when Thomas Eric Duncan brought Ebola to the United States; when an international pandemic appears to be hitting home, efforts are arguably more rooted in security than humanitarian related, as the President clearly noted in his speech.

Also directed by the President, among his four goals to fight Ebola: “to urgently build up a public health system in these countries for the future.” Africa is no outsider to epidemiological outbreaks, as healthcare systems are lacking in both capability and capacity. Diseases such as Ebola tend to permeate and cultivate in emerging states. As Dr. Hans Rosling, professor of international health at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, and other scholars discussed while assisting the MoH in Liberia, Ebola exists due to a general lack of education, lack of healthcare, lack of transportation, lack of information architectures, massive poverty issues, and the resistance to change cultural norms (for example, bodily contact with the deceased during ritual burial practices).

To address the poverty gap, World Health Organization officials and UN Special Envoy on Ebola Dr. David Nabarro lobbied intensely for billions of dollars in long-term development funds to support West African development and economic recovery from the effects of Ebola.13 To counter the effects of Ebola is a daunting task, to say the least. Regardless, if the global community desires Ebola (or other diseases) to be contained at the root cause and not affect their homelands, it must decide to apply appropriate resources for long-term development in these emerging states.

Liberia is a solid venture in that it has potential for independent economic growth based on natural resources such as off-shore petroleum reserves, vast rubber tree plantations, and minerals. Therefore, as a whole these vast natural resources could sustain international investment and help Liberia re-establish the economic growth that was visibly seen prior to the outbreak.

When a conglomerate of the willing put forth resources to a third-party state, it is absolutely imperative that the host nation takes appropriate leadership responsibilities. When a nation such as Liberia invites aid organizations and essentially takes charge, that allows the international community to focus on working more efficiently together. The first impression in attending the MoH-led meetings at the NECC was that this was not a third-world country line ministry, but in fact was a capable emerging economic state. When the leadership of Liberia stepped forward in pulling together the numerous actors and focusing the international community in one direction, it was in fact banding sticks together to make a stronger and unified community. Ebola was defeated by cooperation and collaboration at all levels, but it would not have been so effective if it were not for the competence of the Liberian leadership. JFQ

Notes

1 Analogous settings would be a national-level civil-military operations center or humanitarian operations center.

2 “Remarks by the President on the Ebola Outbreak,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia, September 16, 2014, available at <www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/16/remarks-president-ebola-outbreak>.

3 CDC, “About the Ebola Virus Disease,” available at <www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/about.html>.

4 J.H.T. McPherson, History of Liberia (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1891).

5 United Nations, “UNMIL Response and Assistance to the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD), as of October 13, 2014.”

6 United Nations, “Civil-Military Interaction and Use of Foreign Military and Civil Defense Assets (MCDA) in the Context of the Current Ebola Crisis in West Africa,” v. 1.0, October 20, 2014.

7 Field Manual 3-57, Civil Affairs Operations (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, October 2014).

8 Ross F. Lightsey, “Persistent Engagement: Civil Military Support Elements Operating in CENTCOM,” Special Warfare 23, no. 3 (May–June 2010), 14–23.

9 World Bank, “The Socio-Economic Impacts of Ebola in Liberia,” n.d., available at <www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/publication/socio-economic-impacts-ebola-liberia>.

10 Joint Publication 1-02, Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, November 8, 2010, as amended through November 15, 2015), 93.

11 Ibid.

12 “Remarks by the President.” Emphasis added.

13 Kingsley Ighobor, “Billions Now Required to Save Depleted Healthcare Systems,” Africa Renewal Online, August 2015, available at <www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/august-2015/billions-now-required-save-depleted-healthcare-systems>.